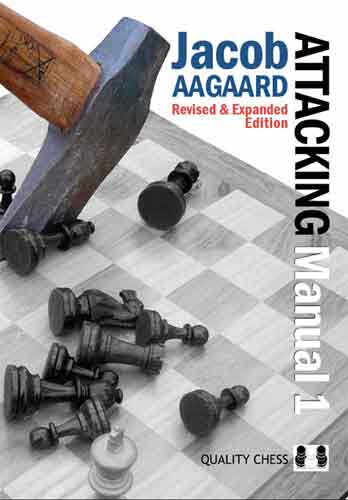

British Champion Jacob Aagaard explains the rules of attack (the exploitation of a dynamic advantage) in an accessible and entertaining style. This groundbreaking work is well balanced between easily understandable examples, exercises and deep analysis. Five years in the making, this book will surely not disappoint. Volume I deals with bringing all the pieces into the action, momentum, colour schemes, strongest and weakest points, evolution/revolution.

This is the first thorough examination of the nature of dynamics in chess. The principles in this book are universal and relevant in every chess game played. The book contains great attacking chess. In lively no-nonsense language, Aagaard explains how the best chess players in the world attack.

Preface

I first started to work on this project back in 2001, when I was thinking about why I disagreed with one, and I stress one, of the ideas in John Watson's monumental work Secrets of Modern Chess Strategy - Advances since Nimzowitsch. The idea I found a little hard to swallow was the notion of "Rule Independence". What John writes is basically that strong players today allow their decisions less and less to be guided by rules. Although this is true if you understand it as, no modern grandmaster will shy away from playing something that looks tempting, just because there is a rule about the knight on the rim being dim, or similar simplifications of how you play chess well. I think this is the main point John wants to make, and I of course completely agree with him.

However, there is a much more complicated question underlying this, which is: why does the move look tempting in the first place.

Some people will like to tell you that developing an understanding of chess is only a matter of being exposed to a high number of positions. If this were true the oldest chess players would also understand chess the best, but as we know this is far from the case. Exposure to a great variety of chess positions is useful, but only if there is some sort of high quality interpretation as well. It is by pondering over higher and higher quality chess material that people in the past came up with observations of general value that they called rules. There was a time (1875 to 1935) where this approach was very popular.

After World War Two few have tried to propose new rules in chess. Those who have were in general chess trainers aiming at helping amateurs to improve, the same goal as a majority of chess literature.

There are of course notable exceptions, but in general the consensus about rules in chess today, is that they are aimed at beginners and have no relevance for high-level play.

Whilst I was thinking about why Watson's conclusion, though logical, did not appeal to me, I continuously stumbled over the word intuition. Being familiar with the books of Mark Dvoretsky and Artur Yusupov I knew that the awareness of rules in chess was not in itself silly. Mark's books are filled with rules, but not with a blind following of them. According to the best Russian traditions everything is analysed closely. Nothing is assumed. According to Mark we might discuss rules in training, but rarely will we find any use for them over the board.

If I ever heard a definition of how to develop intuition, this is it.

Whilst I was reading Watson's book I also noticed that all the rules he referred to were of a static character. It struck me that the understanding of chess that emerged with Steinitz, was born out of a world that believed there were no more important discoveries to be made and that all that remained for science was to fill in the blanks (a common view in the year 1900). Along came Mr. & Mrs. Einstein with their theory of relativity, starting a revolution in science, probably the most defining revolution in a period rife with them! What was meant to be the equivalent in chess was the revolution of the Hypermoderns. But though these ideas were revolutionary, they were still static in their thinking. They were still preoccupied with the dimension of space, though no longer through occupying it, but controlling it.

1935 was the year Nimzowitsch died. It is also the arbitrary year set by Watson as the year when chess started to become what we know today, rule independent.

I have come to the conclusion that a different perspective could be useful. If we see the classical period of chess as a time where the mechanic rules of chess were to some extent worked out, we can choose to see the time after 1935 as the period where the dynamic rules of chess were investigated. This is a simplification, but as something that distinguishes the two periods from each other, it is not entirely stupid.

Having thought this through to the end I started to look closely at the underlying rules of dynamics in chess.

Out of this I developed a set of "rules", first presented in lectures and on two DVDs from ChessBase. These rules should not be understood as a replacement for thinking, as they might have been in the mouth of Dr. Tarrasch, but as something that is worth thinking about at times, and something that is worth internalising in the process of developing your chess intuition.

When these two DVDs were released hardly anyone noticed. Danish IM Steffen Pedersen reviewed them, stating that there was hardly anything new in them. Having found a mistake in my analysias (his analysis engine was faster than mine) he was even a bit unhappy with the general quality of the product, stating, "from Aagaard you would expect more."

I was most likely the only one that saw this as a rave review! Not the least because hardly anyone else will have seen it. I know for a fact that no such comprehensive analysis had been presented on the basis of attacking chess. I accept that there was little that seemed new to Steffen. He is a strong player. But, just like Watson I did not set out to revolutionise modern chess, but to describe what is going on. Some parts of a descriptive theory will naturally be mundane.

There are ideas in here that have not been explained in the same way by anyone before and can therefore be said to be new, but this in itself is not my goal. I wanted to describe dynamics and I have done so by drawing on a lot of other people's ideas far more often than on my own powers of observation. I have tried to give credit in those places where I found it fitting, but most of the ideas are so general that there is no evident source. This is within the spirit of this book, as unlike John Watson, I have set out to write an instructional work. I do not aim to be scientific, like Watson, or to give a scientific approach. My main goal is to be instructive.

005 List of Symbols

006 Bibliography

007 Preface

009 Bring it on - an introduction

025 Bring all your Toys to the Nursery!

049 Don't lose your Breath!

077 Add some Colour to your Play!

093 Size Matters

117 Hit 'em where it hurts!

133 Chewing on Granite!

147 Evolution/Revolution

167 12 Great Attacking Games

219 Watch Yourself take the Next Step!

230 Possible Solutions

260 Index of Games and Fragments |